From the developer

To The Moon is an indie RPG/adventure game, about two doctors traversing through the memories of a dying man to fulfill his last wish.

What we think

To The Moon is one of those games that I want to ask everyone in my vicinity whether or not they’ve played it, so that I can gab away at whether or not we find so-and-so characters sympathetic, and what we think of the game’s conclusion, amongst other numerous tangents that the game unfolds.

The game is more than a sum of its parts, but really teases at the fringes of our personal philosophies on the subconscious mind and emotions, of how it affects our personal identities and understanding of reality. I honestly wish I can debate at length on whether or not the main characters acted morally, and so on. Unfortunately, to do so would mean a full disclosure of all the plot details, and even to go into the grey area of what the game implies.

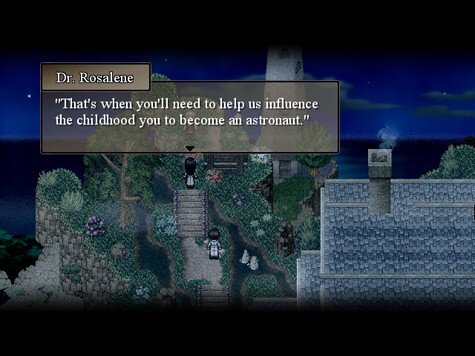

But let me back up a bit to start explaining why I find the game so compelling. To The Moon takes us on a chronicle of Johnny’s life, from his deathbed to his childhood. Although Johnny has lived to a venerable age, he nonetheless holds onto regrets and lost dreams, one which he articulates as “the desire to go to the moon.” As memory transversal agents of Sigmund Corp., Dr. Eva Rosalene and Dr. Neil Watts think that this is pretty daft for a last wish, but they have signed a peculiar contract with Johnny: to reconstruct a fictitious version of an elderly man’s memories that brings to life his deepest desire. This must happen shortly before Johnny draws his last breath, so that he will have the blissful absolution without any jarring fact-versus-fiction consequences.

When we start the game, we come across the innocuous scene of Dr. Eva and Dr. Neil bickering over who gets to do more unsavoury tasks, like manual labour. Their camaraderie seems part of a working relationship in orienting who gets to call the shots. As Eva and Neil step into the unconscious old man’s most recent memory, Eva waves off a question from a cognitive figment of a grey-haired Johnny – on respecting his privacy. There’s usually no helping it, Eva answers, for the doctors will need to know Johnny better than he knows himself. Because the strange last wish is one to which even Johnny doesn’t understand the motivation, the doctors have to be near-clairvoyant so as to peer into Johnny’s most significant memories from childhood to old age.

If you’ll forgive a minor spoiler:

*** We find out early on that bliss escapes Johnny because of his unresolved torment for loved ones who’ve lived with medical conditions. How does one respond to different stimulants, and how does that make him or her seem normal or abnormal? To the Moon engages with these questions both in a compelling and sympathetic manner. Furthermore, the question of consent becomes important. In the case where a person’s identity is impacted by medical and personal intervention, when is it considered necessary and good, and when does it cross the line as an act of coercion? ***

These seem like big questions that we see in the likes of titles like Deus Ex and great, post-modernist visions of society. However, To the Moon takes a different route; one that engages with everyday banter and a small cast of local and familiar characters: Best friends, one true love, and family. Cultural references stay firmly relateable in our present, even despite the futuristic technology that Eva and Neil use to change Johnny’s last memories. This is not a game that explains, in technocratic detail, all of the hopes and nightmares of a hypermodernized world where such a technology is readily available to common folk, but rather Johnny’s world is one that – at least, if we can go by his memories – retains a bit of a small-town mentality, clinging to recurring places and familiar faces.

In terms of purely technical game mechanics, the navigation through a JRPG-styled game-world can feel a bit sticky and unresponsive. Some puzzles can feel like filler in the form of reconstruct-the-image-type mini-games. The JRPG-adventure aesthetics can be a hit or miss, even though it’s clear there’s careful craftsmanship behind them. Generally, the toy-like look grew on me over time, and seemed a good match for the playfully discretionary actions of the two memory doctors. The music is chaste, romantic, and gently uplifting.

But where To the Moon’s gameplay really shines is in its realization of the fickleness of memory. You see, memories can be characterized as self-referential, hence even the most significant memories can appear to leave something out, from an external perspective that thus creates a highly intriguing puzzle, based on remembered words, behaviours and activities. This manner of reverse-narrative structure really persuaded me to read into the characters deeply and become involved in the whys and wherefores of Johnny’s life.

I had stepped into the game expecting melodrama and a labyrinthine, too-hip-to-make-much-sense narrative experience (possibly because the JRPG aesthetics evoke that sort of genre expectation in me), but instead, what I got was much better: a mature and courageous tale that sidles whimsical banter with emotional breakdowns, reflections on personal grievances with future dreams.

For all of these elements combined, it is unerringly accessible. To The Moon is best described as an interactive novel that will stay with me. I can imagine that I will remember certain themes in To The Moon with sudden clarity in seemingly unconnected conversations and activities. Play it, and you will find that you are enveloped into a game world that has a unique standard of storytelling all of its own.

Get the game from the official Freebird Games website for PC here.

[xrr rating=”4.5/5″]

This sounds awesome. I plan on buying this once I get my new laptop, as it seems like something that I would really enjoy. Great review!

Thank you for enjoying the review! I’d be very happy to hear your thoughts once you get the chance to play To the Moon as well.