Developer Summary

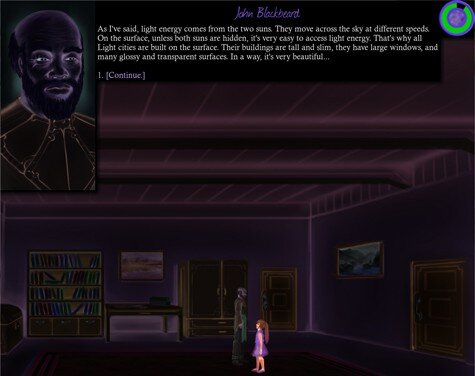

Beneath the planet’s surface, you have to cast aside your assumptions. Darkness is not your enemy, but Light’s army is about to reduce your town to ash. In this 2D interactive narrative, take the role of Raven, an eleven year old girl, who learns that she is the key piece in stopping the inevitable destruction of her town. Now, she has to understand the unfolding events, struggle to solve the challenges facing her, and define herself through difficult choices that will have far-reaching consequences.

As Raven, you will interact with multiple interesting characters, explore a beautiful fantasy world, make lasting decisions, learn Dark magic, and, if you are clever enough, gain infinite power.

What We Think

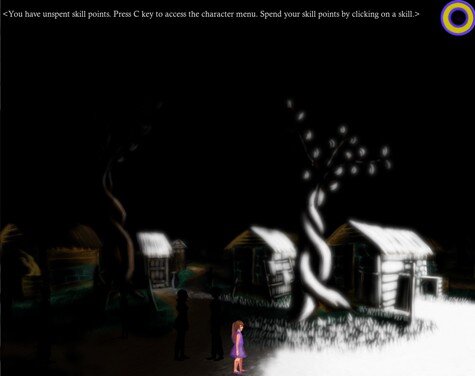

Girl with a Heart Of starts off with an interesting premise. You play as Raven, a young girl who is learning about the roles of her family members as well as the little microcosm of her town of darkness. It is a place that has herethereto given you most necessities that you would want for as a growing child, but it risks being invaded by the Light armies, a natural enemy to you and your kind. This is an interactive story game that orbits around a coming-of-age tale. It subverts the symbolic association that darkness suppresses life, but instead makes it an environment and element where friendship, duty, and honour can flourish.

To that extent, Girl with a Heart Of plays off of the motif of darkness and shadows for this race of magical humans through both storytelling and the playful art style. You find out that the Dark towns are subterranean, and that, the further down in levels, the healthier it is for the Dark race, and therefore all the affluent clusters are there.

However, one cannot dig too deeply into the core of the earth, for it shall lead to a destabilization of the upper levels. This sense of ambiguity between rampant development and sustainability is one of the high points of the narrative experience: It’s a subtle point, one that the developers wisely did not shove down our throats. Instead, it loosely ties into the concerns of the Dark denizens and how they look after their own survival, and their histories with the external threat of the Light race.

However, the depth of fictional engagement can also be threadbare in other contexts. Unfortunately, this is related to themes that are arguably even more central to the development of the story and the choice system within the game. One of the most interesting people you’ll meet is your magical tutor, who tells you about the motivations behind skirmishes and attacks on the Dark town. However often that he emphasizes that the Light is not necessarily bad people, we never get to see this as an example, much less have it presented in shades of grey, or with some moral ambiguity.

This makes it hard to really engage with the urgency of having to protect the Dark against the Light army, and the hows of the approach. For example: Do I agree with the notion of return retaliation against the Light, or keep silent about potentially larger threats from the Light so that my townspeople can rebuild and heal from previous skirmishes? I don’t know, since my sources for understanding the Light is so limited.

The epithet of “show, don’t tell” needs to be utilized much more often in the game: Oftentimes, Raven must listen to other person’s experiences and take it as fact. You never really feel like you are uncovering something for yourself. In other words, you feel like you are being led around – literally, by other people’s words – without a sense of discovery, or the satisfaction of completing a quest. One can claim that the quests are people’s quests: the NPCs’. They successfully tell Raven something in the manner in which they want to obfuscate, tell the truth, ignore, and so forth, and Raven would then take it as gospel.

Another important question arises: How does Raven act and behave that makes her a uniquely female viewpoint, since the title of the game brings it so strongly to my attention? After some introspection, I find that there’s little beyond naming certain game mechanics as “heart”, “love”, “truth”, and so forth that makes it appear feminine.

There is no moment in the game that stood out to me as relating to girl empowerment particularly. A boy child can be substituted in without breaking a sweat, which renders gender an unnecessary emphasis. Raven merely obediently learns from a few authority figures in order to help change the course of the town’s fate. For me, that just breaks the suspension of disbelief that dialogue options actually have any lasting affect on the outcome, and the narrative world just doesn’t have this “lived-in” feel that an insular town should provide.

The first playthrough still offers some compelling narrative exploration. However, by the time I have sensed that I am near the end of the game, I felt that Girl with a Heart Of didn’t live up to its initial promise. Although the fictional world’s premise is initially exciting, its uneven narrative makes the turning point of the story unrewarding and estranged its development.

[xrr rating=”3/5″]

I just have to ask. What, exactly, could a character do that would make her “uniquely female”? Cry? Cuddle a puppy? Get her period? The character being a girl makes her female. You seem o have read the title, seen the words “girl” and “heart” (which you inexplicably assigned “girlyness”, completely out of context), and assumed the main character would be prancing around with ponies or something. I am female, and most of the things people say need to be done to a character’s personality and experiences to “make her female” are completely unrelatable to me. Usually male characters don’t act “uniquely male”, they act like humans, and do what a human would do. So why does a female character have to find some other, “girly” way of doing it? Maybe I, and all the other women I know, are just men with boobs, because every time a female character acts the way I think is correct, that’s what she gets called.

Most male characters in any media could easily be replaced with a female.

Hi Xi,

Thank you first off for taking the time to comment. From what I can tell, this is a topic that is something you feel quite strongly about. However, I believe that you have misconstrued my argument and took two lines in isolation to everything else that I’ve expressed. In fact, your opinion is agreeing with me, rather than against.

This line of mine: “I find that there’s little beyond naming certain game mechanics as “heart”, “love”, “truth”, and so forth that makes it appear feminine.” Perhaps the “appears” should be emphasized: the usage of heart, love, truth, and so on as game mechanics is obviously a conscious choice on the part of the developers, to generate a certain visual experience. As you pointed out, heart may also exist with male protagonists, such as Link from the Zelda series. However, for Girl With A Heart Of, the developers have made sure that it is magic and “heart” that you have access to as powers. It is not melee weapons in addition, for example.

That kind of symbolic usage of heart, truth, deceit as “magical assets” means very little in isolation. But the heart of my criticism of Girl With A Heart Of is that it never parleys a sense that Raven is growing, learning, and starting to have her own influence in the world. She’s always been a pawn to machinations outside her own control, which is not what I think was an intentional sentiment. The game wants you to feel that Raven has a lot to overcome, but it falls short, because she’s only doing what other people tell her to do. And, not only is the character either submissive or basically doesn’t change more than superficially in the game (the only change is “Magic”; There’s no “character arc”), but the dialogue choices/gameplay choices doesn’t feel like it matters. Compounded with the fact that I should reasonably expect this title to be about “a girl growing up to become somebody/a coming-of-age story”, I felt that I came away from it pretty disappointed.

So, what are we left with if we have no personal character development? We’re left with the little symbols and aesthetics that girls are typically associated with: Pastel colours, hearts, trinkets, bouncing pigtails and bubble skirts. I’m no more engaged with that as you are with ponies and puppies. Honestly, if this was a text-based game and you took away the gender pronouns, you wouldn’t know if Raven is a boy or a girl.

I disagree, however, with your justification that male characters and female characters can be replaced by each other. As non-archetypal female characters are more of a rarity in video games, I would say this: Think of a film or book where there’s a female character that you are very sympathetic to, or whom you think is very realistic and believable.

Some of the female characters that I find most compelling are ones that I don’t even agree with, on a moral level. Yet I find that they are believable because they give a unique perspective given their own social place in the world – even if the world is fantasy and sci-fi. That’s what I mean when I say that there’s a lived-in feel to people and places: There’s a sense that this person has a history and is motivated by a whole web of past experiences. That kind of strength of character and narrative development can create a relateable kind of personality that can be rife with uncertainty, and that’s what makes it interesting. That’s what makes coming of life stories particularly interesting, especially when the female character doesn’t come from an expectation of privilege as associated with the dominant Masculine counterpart.

I could go on, especially with media and even games where I could argue that there is a feminist appeal to them. Simply put, Girl With A Heart Of is very conventional & obvious in the way that it Looks (psychoanalytic use of the term), without asking questions about why it uses the aesthetics that it does, specific to the narrative at hand. Ie: Raven is a visible object to the player, and with Objectified/symbolic parts, but that loss of autonomy is never questioned/emphasized/deconstructed/made into a tragicomedy. To get into discussing that further, I will have to explain a lot of media theory and structuralist philosophy backbone, which may or may not be of interest to you.

You make a very good reply. I do realize that I agree with everything else you’ve said.

Quibbling over how to make a character female just sort of sets me off. The female protagonists I relate to the best are usually the female option that was probably just tacked on as an afterthought to a character written as male. Characters written to be specifically female tend to have stereotypical characteristics that I would prefer to see less of. Yes, this is a subject I feel strongly about, I guess because of the lack of good female characters, the excuses and puzzling over making “girl” games or female characters when all it would usually take to satisfy me is a change of character model.

I feel I should apologize though, my comment only addressed the one part of your article that touched an admittedly oversensitive nerve with me (as a female gamer you may understand why), when I found the rest to be very good and insightful.

No worries, I understand where you’re coming from. And I shouldn’t expect anyone to read super closely to every line that’s written – it’s a review, after all, not an essay! And I appreciate the candidness and honesty in our discussion, of course.

I have a bit of this idealist streak in me that says, ‘Just because stereotypical girls in games are the norm today, doesn’t mean it’ll always be like that.’ That’s part of the reason that I’m very intrigued by the indie game marketplace as well as the AAA top-budget games. Indies may have much more freedom of design choices when there’s not tens of millions of dollars on the line, but there’s also so much more polish involved with a large studio’s team. So, I’m not losing heart yet that there might yet be female characters that have an interesting role to play and worlds to influence, in both fields.

Honestly, my opinion is that a good part of the answer might be in having more women in game publishing and development, in positions where they are specialists and decision-makers.