The Novelist – What We Think:

The best thing about The Novelist is the writing. That’s probably appropriate, even if we don’t get to read the novel in question. The game focuses instead on an interpersonal family drama playing out across letters, newspaper clippings, and other various forms of text. Those missives are often excellent, by turns poignant, sincere, and tragically observant throughout the first two-thirds of the game.

But that last third is problematic. The Novelist gradually falls apart once the human drama loses touch with reality and the supernatural conceit sends an otherwise grounded plot careening into the realm of melodrama.

Ghost In The Machine versus Fly On the Wall

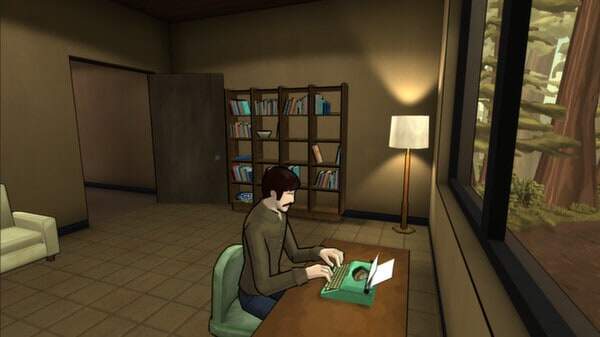

The Novelist chronicles one summer in the lives of the Kaplan family. Dan is the titular novelist. Linda is an aspiring painter and Dan’s wife. Tommy is their son, currently struggling in school. They’ve just moved into a rustic seaside house to sort out their problems while Dan tries to complete his book.

You, meanwhile, are a ghost, a benevolent spirit haunting the premises looking for clues to uncover what each of the three characters want. You then decide whose priorities take precedence and whisper suggestions in Dan’s ear while he sleeps. One character gets everything, the second gets a disappointing compromise, and the third character gets nothing, all according to your explicit recommendations.

The Novelist draws its emotional power from that choose-your-own construction, showing you paths that could be to remind you that they won’t. The Kaplans shuffle about the house while you lurk unseen, and the graphics and controls – though unwieldy – offer enough functionality to encourage you to engage with the family rather than the mechanics.

The Kaplans demonstrate that best intentions are not enough when measured against time. If you relate to Dan’s professional ambitions and attempt to write the best novel you can, your success comes at the expense of Tommy and Linda’s emotional wellbeing.

Choose Your Own Neglect

That awareness makes the game affecting. Bad outcomes happen because you chose to allow them, not because they were unavoidable. You know exactly what you would do given another opportunity, and that knowledge – coupled with the regret that you still didn’t take Tommy to the air show – makes the resulting unhappiness all the more tragic. It lends the weight of consequence to every decision.

The technique is particularly effective given the conventions of the medium. Video games – even those that claim to prioritize moral ambiguity within the narrative –have conditioned us to expect a ‘best ending’ that can be unlocked when you search every corner and pursue every line of dialogue.

The Novelist deliberately denies that sense of completionism, only allowing you to choose A, B, or C to suggest that it’s impossible to achieve the satisfaction that we expect from and. We always want more, but no matter how desperately we crave it, that ideal is unattainable. You don’t get to make everyone happy.

Little Boy Blue and the Man in the Moon

So with that in mind, do you work on your book or a toy car for your son? Do you help Tommy with his homework or do you share a bottle of wine with your wife to try to resurrect a failing marriage?

They’re mundane troubles that illustrate the challenge of juggling disparate interests in a cohabiting relationship. Witnessing Tommy’s descent into bitter neglect can be heartbreaking, so why is it easier to tolerate when your career is thriving? And why should that be the case?

The Novelist preys on those doubts to generate guilt, and while it can be a bit heavy-handed, it works because the day-to-day concerns are recognizable. We all have to balance our interests against the interests of those around us.

Love Don’t Live Here Anymore

It’s therefore unfortunate that the game loses its impact when it tries to raise the stakes. The first few chapters are exercises in restraint. The trials are manageable, as are the character’s reactions. If you focus on your book, Linda’s diary will be hurt but compassionate, while Dan will frequently indicate that he wants nothing more than to patch things up with Linda and Tommy.

You get the sense that despite their faults, these people care deeply about each other, and Dan and Linda are smart enough for empathy. Much of their disappointment is couched in conciliatory dialogue that indicates that all parties want to stick together.

Since their interests coincide with those of the player, the game begins to feel contrived when it shifts gears to ensure that everyone is either alive or dead inside. Characters who were originally taking things one day at a time suddenly decide that this is how things must be forever, even as the writing style insists that Dan and Linda are entirely too rational to view the world through such an adolescent lens.

The logical gaps eventually become too cavernous to ignore. One of the later chapters revolves around a drinking problem never previously referred to and never referenced again, and the disconnect makes the whole enterprise feel silly. Depending on your choices, you’re either the greatest American novelist or a complete burnout, and the fortunes of your family are similarly all-or-nothing.

The Family That Acquiesces Together…

That’s where the game’s setup starts to work against it. It’s implied that since the setting is somehow supernatural, choices here have more determinative significance than choices made elsewhere. It’s reminiscent of the movie Click, insofar as we’re supposed to swallow a bit of outlandishness along with the premise.

But that’s an easier sell in a romantic comedy with Adam Sandler than a video game with literary aspirations. The Novelist’s subdued introduction establishes a more contextual tone as Linda and Dan acknowledge prior events without being defined by them. They express hope for the future while recognizing that circumstances change throughout a career and a marriage.

That’s why it’s so unexpected when they decide that the way things are for the last three weeks of one pressurized summer will dictate the contours of the rest of their lives. Following two in-game months of relatable normalcy, the accelerated conclusion rings hollow, and undercuts much of the ambiguity that came before it.

Book ’em, Danno

The Novelist is still worth a look, largely because the writing and the structure are complex enough to suggest an entire spectrum of possible reactions. The game has plenty to say about relationships weighed against personal aspirations. It just finds more meaning in life’s smaller moments than it does in grand designs.

The Novelist – Official Site

Get The Novelist on Steam

[xrr rating=”4/5″]