Keys of a Gamespace – Developer Summary

Keys of a Gamespace offers a stab into a rare genre of gaming – of theory and psychology. It aims at encouraging gamers view video games as an artistic medium that reflects the concerns and issues of current society. However, this attempt remains to be a stab in the dark. Both the game’s fictional content and game mechanics do not inspire conversation about the gaming experience and its connection to our everyday experiences and philosophies. Instead, it risks alienating the very people who are willing to see video games as thought-provoking.

The best narrative games have, as an expressive medium, delivered visceral and emotional experiences. This can be constructed through a marriage of expository or gradual narrative and well-paced game mechanics that follow from a reasonable expectation of the logic of the game. The narrative does not need to be full of complex loops and intrigue; A fragment of a walk-in-a-life or an elemental conflict-resolution set-up can be just as effective. However, it has to express some kind of narrativization that works in tandem with the goals of the game. In practical terms, the puzzles just have to make sense in how they are solved. For Keys of a Gamespace, its goal is to engage the gamer in reflecting upon difficult social choices through Adventure Game conventions.

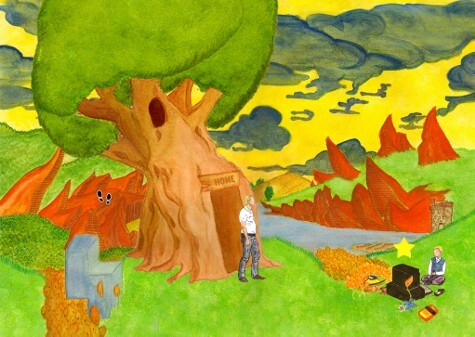

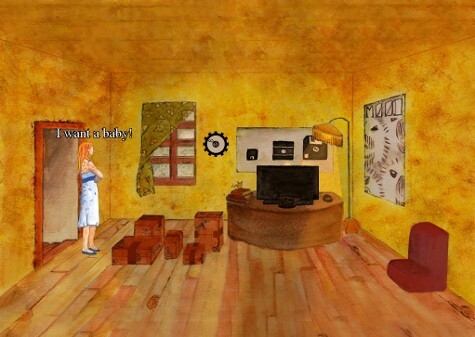

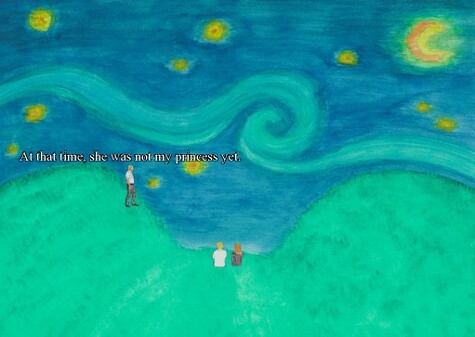

We are introduced to Sébastien, who is being scolded roundly by his girlfriend about his indifference in having a baby with her, when all he wants to do is play video games. The domestic confrontation is rather one-sided, as Sébastien’s mostly obscured by his large computer monitor. The girlfriend gives Sébastien the ultimatum that he must get his act together or she will leave him, which prompts Sébastien’s imagining of his psychological space and starts into the heart of the game. Sébastien’s psychic space is comprised of doors into key years and memories of his life. These scenes from childhood to adulthood have a dreamy, painterly aesthetic to them, clearly reinterpreted through poetry, games, and art. At the end of this summary reflection, we are asked to make a decision on how Sébastien can find closure to his phantoms.

A small bit of explication is needed here: Keys deals with the difficult themes of abuse and neglect. Because of this, I want to look extra diligently at the forms of representation and identities in this game. Even as I am aware that the developer from the University of Metz is primarily engaged in semiotics and media studies research, I aim to examine the game as the core of my review rather than the motivations of the team that made it, because I can only half-guess at what that might be (French language barrier notwithstanding).

First of all, it is stated on the website that Keys clearly has didactic aims. However, it shies away from presenting them as such and leaves it as an afterthought – literally, until the last frame of the game as a block of text. This brevity is particularly discouraging, and makes it appear as though it had no particular hopes for keeping the audience’s attention if its loaded philosophical aims were more evenly distributed to move the game forward.

Its cookie-cutter melodrama also falls from this attitude of brevity. For something with such mature subject matter, we are being treated to bite-sized presentations that are no more elucidating than a gossip column. We are given an opportunity to take choices in the game, but I can’t help but think that the whole game interaction leading up to it only highlights the protagonist’s blindness and lack of observation.

Indeed, the game seems to suggest that it celebrates free choice, just as my own gameplay experience seem to suggest its opposite. My very choice feels not so much like it is bounded by sociological interpretation as it feels like I am merely inputting suggestions into an internet personality quiz. The dialogue writing (and perhaps its English translation) lends itself to this looseness – it is neither intimate not expository in a distinctly biopic tone, but is remarkably forgettable for its inanity.

For a game that presents itself as self-aware and expressive, I stepped into the game with high expectations of restrained storytelling and self-reflexive emotional scenarios. Unfortunately, the game appears to tell, more than show. Moreover, it is hindered by stock characters and a melodramatic narrative and mode of exposition. For example, Sébastien’s mother remains unconscious for the entirety of the game, with the exception of uttering how horrible everything is in her life. This kind of unreasonable stagnation does not give us any further insight into her impact on Sébastien’s life. Instead, she is only rendered as a mouthpiece for one particular instance, but is presented with no will of her own. This lack of character development is repeated amongst other characters, particularly women. The lack of care in presenting these characters makes it difficult for me to take the game seriously as a mode for exploring ethics.

More simply, the game just doesn’t try to make any of characters familiar to the gamer, including Sébastien himself. Considering that we’re in Sébastien’s psychic space, one would imagine that Sébastien may fixate on unruly, unusual, and otherwise repressed things. What we end up having is very little observation, or self-recollection. We actually come to understand or interpret very little of Sébastien himself. We are also never implicated into the question of how reliable Sébastien is as a narrator – whether the entirety of the game is a little lie that the protagonist has told himself (After all, why would he even explore his own past for this female partner whom he barely cared to characterize in his own psyche?) Certainly it can be read as much, if we ignore all of the commentary that has been written on the game by its creators. However, this interpretation exists because there is an absence of character development, not because of it.

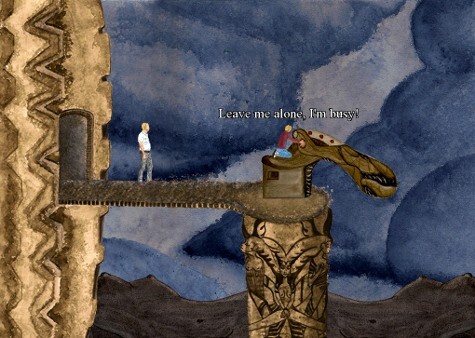

This is compounded with poor game mechanics design in conjunction with its highly respectable didactic aims. The ambling animations of a third-person adventure game may be more suited towards a biopic than as a representation of a character’s psychic space. The slot A-in-B puzzles also feel like a guessing game because of the abstract nature of dreams and memories. Additionally, characters’ words have no rhyme or reason in terms where they are written on the screen, adding to the game’s rough edges.

In contrast to the weakness in the game mechanics, the musical score and sounds are atmospheric. The score very ably combined silences, sound effects, and music to great affect. The handcrafted, watercolour illustration style also appeal to the fantastic and unpredictable representation of the psyche.

To put it simply, Keys is a game that is highly necessary and needs to exist, because it fills that near-absence of titles in the theory-based game genre. However, the limited scope of its content, presentation, and design interactivity undermines the very goals that it sets out to achieve: to enable a thorough and deep exploration of ethical and social contradictions of our times. Instead, its haphazard storytelling, presentation, and game mechanics make it campy rather than serious.

[xrr rating=”2/5″]